In the coming months, Traverse Area District Library (TADL) will become the home of the regional archives formerly maintained by the History Center of Traverse City (HCTC). In response to that event, reference librarians at TADL have received a number of questions. Since the Grand Traverse Journal is a forum for sharing knowledge, let me take the opportunity to describe an archives, explain its functions, and tell how having an archives available at TADL is important to library visitors and patrons. Afterwards the HCTC will supply a brief history of its archives.

What is an archives?

Archives are similar to libraries. They exist to make their collections of information available to people, but differ from libraries in both the types of materials they hold, and the way materials are accessed. Archives concern themselves with future use, or the “second life” of information.

All information, whether it remains in your head or is recorded on a physical medium, has a first and second life. That life cycle can vary, depending on what the information is and how the information is used. The first life of information covers the time the information is immediately relevant, and the second life covers the time that information has no immediate relevancy, but may have some future use.

Memorizing a restaurant phone number has a short first life, perhaps 20 seconds, and a long second life, where it may get filed in your memory bank for recall at some later date. Your birth certificate has a longer first life, as the information it records is good to have on hand for the length of your life, but it also has a second life. Perhaps a distant descendant will need that information to record in the family tree, or researchers will use your information to explore health issues of the past.

An archives is a place to store, preserve, and make available information that is in its second life to people who need that information. Information held in an archives is usually unique.

How does an archives function?

Most people keep their own personal records, such as tax filings, court papers, wills and trusts, and the organization and management of your personal archives is a thing easily managed. You create a finite set of papers, probably organizing them using folders and a filing cabinet or two, and within five minutes of searching, the document you are looking for is found.

Now, imagine if you cared for all the personal records of every member of your extended family. You might need to come up with a system for making sure Aunt Joan’s documents stay with her other files, and Aunt Claire’s stays with hers. Most archives operate this way; We call it maintaining “provenance,” that is, keeping things of the same origin together. An alternative would be to separate like documents (perhaps putting everyone’s student loan information in one folder), but this method destroys the context of their creation, and limits our ability to arrange and describe the archives effectively. An even more amusing alternative is to throw it all in the middle of floor, but none of your family members would thank you for that. How could they ever find the document they were looking for?

We’ve just described basically how an archives functions, but let’s break it down into steps:

- An object (usually a document, but it could be a bound volume (like a school yearbook) or a three-dimensional object, (like a rug beater from the 1910s)), is brought in to the archives by a donor (this person could be a staff member for an organization, a family member, or whoever is in possession of the object and deems it valuable enough to save).

- The object is appraised by the archivist (that is, the person running the archives). Archivists are looking for objects that add to our understanding of the past, and are not usually trained to appraise objects for their value. The appraisal process raises a number of questions: What does this object tell us about the past? Is it unique, or do I have a bunch of similar objects already? Is it in good condition, or is it very fragile and likely to take money and time performing conservation work?

- The object is accepted into the archives, or returned to the donor. If accepted, the archivist sits down with the donor and explains the Donor Form, in which the donor (typically) signs over their legal claim to the object. The Donor Form can also sign over other rights, permitting the archivist to provide access to the object, perform conservation work, and more.

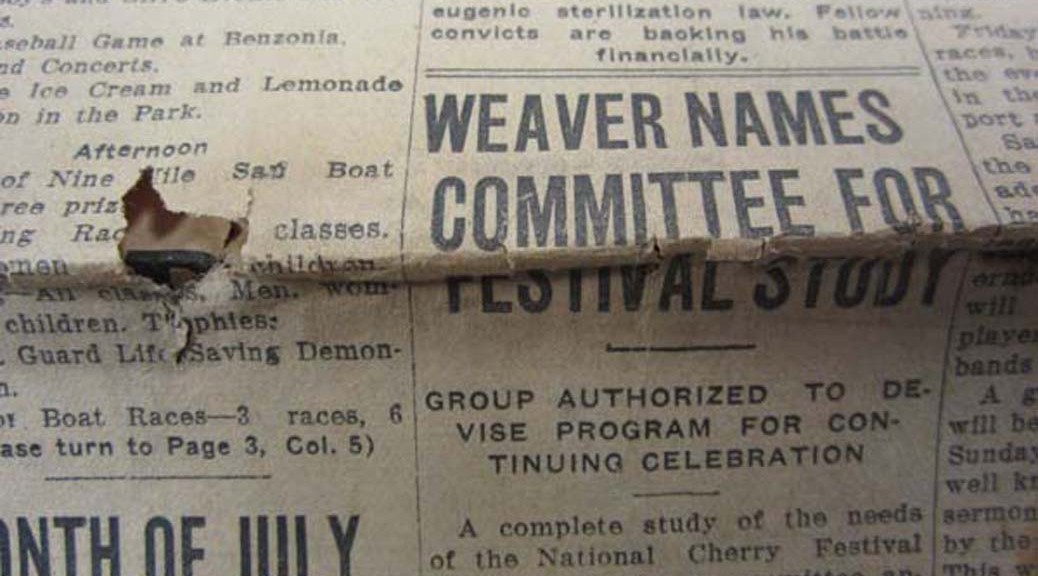

- The object is processed into the collection. This is when the archivist catalogs and describes the object. That description is placed into a database of all the objects in the archives, so that researchers can search the database for objects that might have the information they are looking for. Finding aids are the most common tool created by archivists to help researchers find objects that meet their information needs. Finding aids are descriptive indexes, inventories or guides created during the processing of a collection to describe a collection’s contents. You can see examples of findings aids created by Traverse Area District Library to better understand how objects are processed: Finding Aids.

- The object is accessed by a researcher, and information is culled from it. After discovering the object in the database, the researcher informs the archivist that they would like to see it. For the security of the collection, the archivist will hold on to a piece of identification while the researcher is working. The researcher is also informed of the basic rules for handling archival materials, which includes using pencil only, not to write directly on materials, turning one page at a time, using gloves to handle photographs, and other rules as the situation calls for it. The archivist then pulls the object from its location, and the researcher is given time to look the material over and see if the information it contains answers their research question.

How will the transfer of the archives to TADL affect me?

For you, our patrons and researchers, the transfer of the archives means the largest known collections of published and unpublished works concerning our local heritage will now be housed in one building. It also means our collective history will be retained in the Grand Traverse Region, rather than being parceled out to other archival institutions. The archives, like all library materials, will be accessible to all our visitors. As stated by TADL board president Jason Gillman in a recent Record-Eagle forum piece, “preservation and display of the area’s history will be an added bonus for library patrons and visitors.”

As the steward of this public collection, the HCTC’s largely volunteer crew and lone professional archivist made the archives accessible, maintained the collections and improved them with new acquisitions. As the new steward, TADL is both professionally and technically prepared to take on the archives. In addition to those tasks listed above, TADL is also committed to growing and improving the online image archives as well, providing unparalleled access to both local and remote researchers.

You can also expect the HCTC to stay involved and especially to promote history education for all. As stated by Stephen Sicilaino, Chair of the HCTC Board, “The Board believes that with the transfer of the archives to TADL, the History Center will be able to become a stronger organization and more effectively meet its mission to protect, preserve, and present the history of the region. We will continue to work with TADL on preserving the archives and we will have greater ability to present the history of the area through programs and publications” (Open letter to the membership, November 2015).

Your editors hope you will join us for our HCTC and TADL jointly-sponsored monthly history programs, which take place on the third Sunday of the month, at 2pm. In 2016, topics will range from lumbering to labor strikes, and all points in between!

History of the Grand Traverse Archives (provided by the HCTC)

The archives trace their beginnings to Traverse City’s Old Settler’s Association, a social club organized in the 1920’s, by the area’s original white settlers. This group eventually became the Grand Traverse Historical Society (GTHS) and focused primarily on social gatherings and educational presentations. In the 1980’s the GTHS joined with the Pioneer Study Center, a public archives started in 1978 at Pathfinder School. The new organization, the Grand Traverse Pioneer and Historical Society, received thousands of photographs and historical documents from the Pioneer Study Center. The collection was variously located in the basement of the Grand Traverse County Courthouse, the basement of the City-County Building, and above a store front on Front Street. In 2005 it moved into state-of-the-art facilities in the newly opened Grand Traverse Heritage Center, located at the renovated Carnegie Library building on Sixth street, the original Traverse City Public Library. The Society changed its name to the Traverse Area Historical Society in 2008.

In 2010, the Society merged with another non-profit, the Friends of the Con Foster Museum, largely because the two organizations held similar missions, to foster historical education and preserve our local history, and the renovated Carnegie provided space for both the Museum collections, as well as the Archives. The combined organizations became the History Center of Traverse City. Since receiving the initial donation of the Pioneer Study Center archives in 1978, the organization (whatever name it was operating under) continued to collect donated materials to improve the archives’ holdings.

Amy Barritt is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal, and Special Collections Librarian at Traverse Area District Library. Special thanks to Peg Siciliano, who provided the history of the archives to date.