Close to the railroad trestle across the Boardman River at Eighth Street, a large patch of ragweed grows tall, some plants reaching five feet high. It covers disturbed ground with a dense tangle of leaves and stems, never gracing the landscape with a hint of color. Not particular to good soil or poor, it grows wherever the soil has been disturbed, only reaching gigantic proportions under the best conditions. Though an annual, it comes up year after year unless attention is paid to its control.

Ragweed will eventually go away as other plants move in to squeeze it out, but its retreat is often slow and uneven. Uprooting the plant gets rid of it for a scant year or two, but as long as the ground is bare of other plants, it will come back. The only real solution is to seed an area with something more desirable- grass or shrubs, for example. That, of course, involves a plan, disciplined labor, and money for seed. In the past Traverse City applied a simpler remedy: paying children to eradicate ragweed. While spreading wealth among the youth, it never quite did the job. Ragweed flourishes now as it always has.

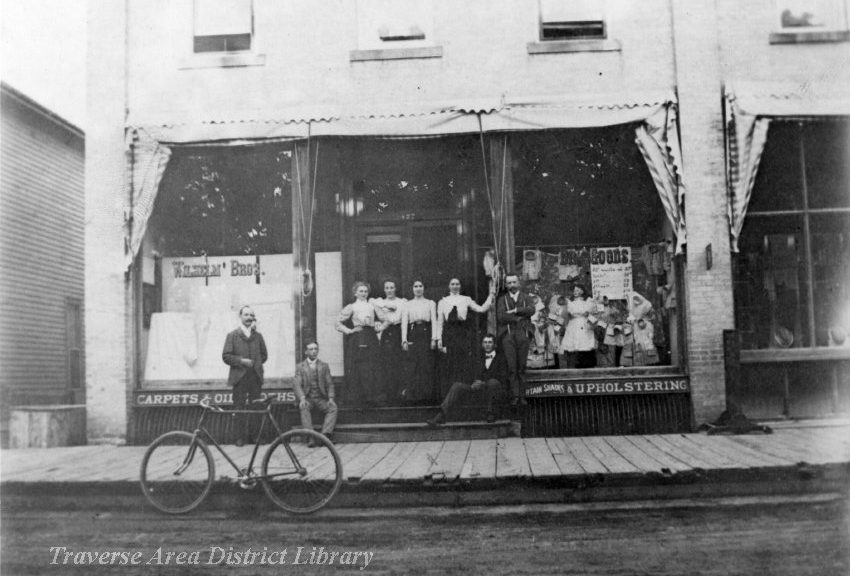

With the building of the homes, railroads, farms, docks, and factories that replaced the great pine forests of the Traverse area came the pests that survive and thrive on the leavings of humankind: spilled grain from a mill, garbage left beside a house, a dump sited near residences, the river with its flowing cargo of waste and dead fish, horse manure that nourished clouds of floes. Rat and sparrows, locusts and flies- even unwanted plants like ragweed- arrived in our town and, like their fellow human immigrants, settled down to make decent homes for themselves. Seeing no future in the Old World, Norway rats fled to America, obtaining free transportation aboard boats shipping seed corn and food to the New World. Invited by certain misguided individuals who missed the birds of Europe, house sparrows were set free on the East Coast of the United States in 1852. It did not take them long to find Traverse City for it is noted in a Record-Eagle article of 1923 that a bounty of two cents was offered for every sparrow carcass brought in to the examiners.

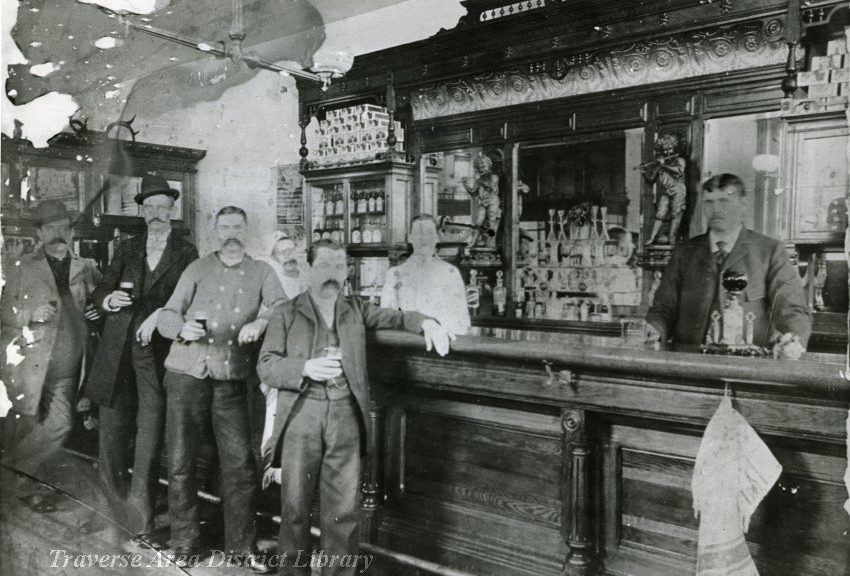

Firearm control of animals was not confined to sparrows. Rats brought a richer reward than sparrows to young marksmen: ten cents per rat, the tail being sufficient evidence of a corpse. Of course, a wiser, and less violent approach would have been to make food unavailable to rodents and birds, but that simple idea would require time to take root in people’s consciousness. After all, shooting pests provides a certain satisfaction since success is easily measured by body counts, while eliminating food sources does not carry the same panache. Besides, the hunter’s instinct is never far from the surface in small towns of the American Middle West.

Undeserving of compassion, these hapless creatures were classified as “vermin” and were hated because they spread disease and filth about the city. More than the threat to public health they posed was the appearance of poverty and ugliness. They represented an insult to the civilization of a fine city: Traverse City, Michigan. To affronted townspeople, the only good sparrow was a dead sparrow; the only good rat was a dead rat.

The Record-Eagle joined the battle against vermin in 1924. Fresh from victories over the rat populations of Manistee and Muskegon, one Helen Caldwell became the field general for a local rat extermination campaign. Beneath a picture of Caldwell, the newspaper waxed poetic about the campaign:

Rodents and such were gathering fast,

When through the village street they passed

A youth [Caldwell] whose banner bore that strange device,

“Rat Poison!”

Straightaway unto Bill Hobbs she turned,

And he it was who firstly learned,

The power behind those magic words,

“Rat Poison!”

And he took her to the paper place,

Where the Record-Eagle entered the race

To shout and cry from the top of the page,

“Rat Poison!”

Then to the mayor she hied her way,

And with him also she had her say,

Which was and is and will be, too

“Rat Poison!”

The board of health sat on the case,

And a smile beamed over Doc Holliday’s face,

As he decreed for the city’s pests

“Rat Poison!”

Barium carbonate was the poison of choice. It was to be mixed with meat, cheese, cereals and cake- even fresh fruit like bananas and cantaloupe (apparently, rat insisted on a smorgasbord of delicacies). Care would be taken to keep the poison bait away from pets (and children, one would presume). In case an accident should occur, the sufferer should ingest Rochelle or Epson salts as an emetic.

The mayor of Traverse City, James T. Milliken, issued a proclamation in support of the rat extermination program:

Inasmuch as every person in the city is supporting two rats at a cost of $1.82 each and inasmuch as this expense can be eliminated, it is with considerable enthusiasm that I endorse the rat extermination campaign which is now being waged in Traverse City.

In endorsing this campaign I also designate the dates from July 31 to August 9 as “Rat Killing Week” and urge every citizen, including every boy and every girl, to join this movement and make Traverse City a ratless city.

With such publicity, the campaign could not but succeed. A week into the campaign the Record-Eagle reported, “Traverse City’s rat population has decreased by leaps and bounds almost overnight, the rats in their poison throes, leaping and bounding out into the open air to die by the dozens.” The mayor’s call to the boys and girls had brought in ample evidence of rat slaughter: rat tails by the dozens were turned over to the local Rotary Club and prizes and rewards were distributed to the children. The sales of barium carbonate had gone through the roof at local druggists and there was heavy traffic in rat traps in hardware stores around the area. Everyone agreed that, if the City was not entirely “rat-free,” at lease a dent had been made in the rat population. Miss Caldwell would carve another notch in her belt as she left town.

Rats were not the only pestilence afflicting the City. In some years grasshoppers increased beyond the bounds of human tolerance, their numbers soaring as they fed in scrub land that replaced the pine and hardwood forests that occupied the land in the nineteenth century. Authorities did not mess around in doing them in: Arsenic was the designated poison. To this day, land close to the City is contaminated with arsenic residue, a substance deemed so toxic by the EPA that severe restrictions have been placed upon its use.

Animals seen as predators of game birds and sport fish were dealt with sternly. Crows in particular were targeted as a nuisance since they attached young ruffed grouse whenever opportunity presented itself. Consequently, in one year (1937) 2100 of them were killed by teams of marksmen composed of members of the local Dog and Sportsman Club. Mergansers, (diving ducks) were shot in large numbers on the Bay and inland lakes because of their appetite for fish. Even fish were not immune from human prejudices: it was reported that a half ton of dogfish (bowfin) were speared in Lake Leelanau in 1930. There were called “obnoxious” by the perpetrators, presumably because they were not good to eat and competed with more desirable fish for food.

Animals were not alone in suffering punishment for getting in the way of human desires. Poplar trees were condemned within the City limits in the early twenties. Their crime? Their roots readily invaded sewage lines, sometimes causing unsanitary back-ups into people’s basements. Dr. A.G. Holliday, city health officer, insisted on strict enforcement of an existing anti-poplar ordinance after the City was forced to expend 200 to 500 dollars for the clearing of the roots from the sewers, an expense that would not be tolerated. It was noted in the paper that some citizens- in particular certain residents living on Sixth Street- would not suffer gladly this insult to their poplars. It is not known if their trees received a reprieve from the death penalty.

Casual observation about town nowadays reveals a plentiful growth of poplars of several varieties. Perhaps the vicious nature of the plant has cooled- or else city sewer system pipes are impervious to their probing roots. In any case, poplars have gained a small measure of respect- at least from some property owners.

Ragweed was another “planta non grata”. With its abundant pollen, it was known to cause hay fever, a problem back in the twenties as now. Northern Michigan was considered to be haven from the noxious weed. Hay fever sufferers flocked here in summer to find relief from the sneezing and runny nose they experienced in Illinois, Ohio, and Southern Michigan. In 1929 the City quickly went through its ragweed control budget of one hundred dollars in dealing out direct payments to children who would get ten cents for every hundred plants they brought in. Later, in the early fifties, movie tickets were distributed for armloads of ragweed which were carefully weighed to determine the number of tickets earned. On Occassion children who had allowed their plants to dry at home overnight were disappointed at the low weight totals of the wilted plants. It did not take long for them to understand that fresh ragweed weighed more.

The battle agains pests has hardly abated. In recent years Gypsy moths were subjected to airborne application of the bacterial spray Thuricide, that treatment saving the city’s ancient oaks and maples. Skunks invaded one city neighborhood shortly afterwards and began a miniature city of their own. Only a trapping program thwarted their plans for domination.

Invasive plants have marched into town, one species after another. Purple loosestrife was poised to cover every wetland until beetles were brought in to bring it under control. Baby’s breath, an escaped garden dweller, threatened to take over abandoned land especially by the railroad tracks. Autumn olive and buckthorn covered many acres inside and outside the city. Finally, an eight-foot high grass, Phragmites (aka, the common reed), has been recently sentenced to die through applications of topical poison. It cannot be allowed to take root upon the shores of lakes, river, and the Bay or else it will crowd out the natives.

There is a pattern of our responses to Nature’s assaults. At first, we call in the Army, Navy, and Air Force and give the battle all we’ve got. After time and expense, we back off, wondering if we cannot co-exist. Finally, we forget there ever was a problem and regard the pest as another somewhat disreputable member of the neighborhood. Maybe that should have been our approach from the beginning: acceptance of the pest’s right to exist, while denying it free rein to raise havoc. Respect within firmly set bounds. For that matter, it’s not a bad plan for humans. After all, we are an invasive species, too.

“Rats and Sparrows, Poplar and Ragweed: Traverse City versus Nature,” was originally published in Richard Fidler’s book, Gateways to Grand Traverse Past, recently republished under Mission Point Press in July 2017. Gateways is for sale at Horizon Books, Traverse City, and on Amazon.